|

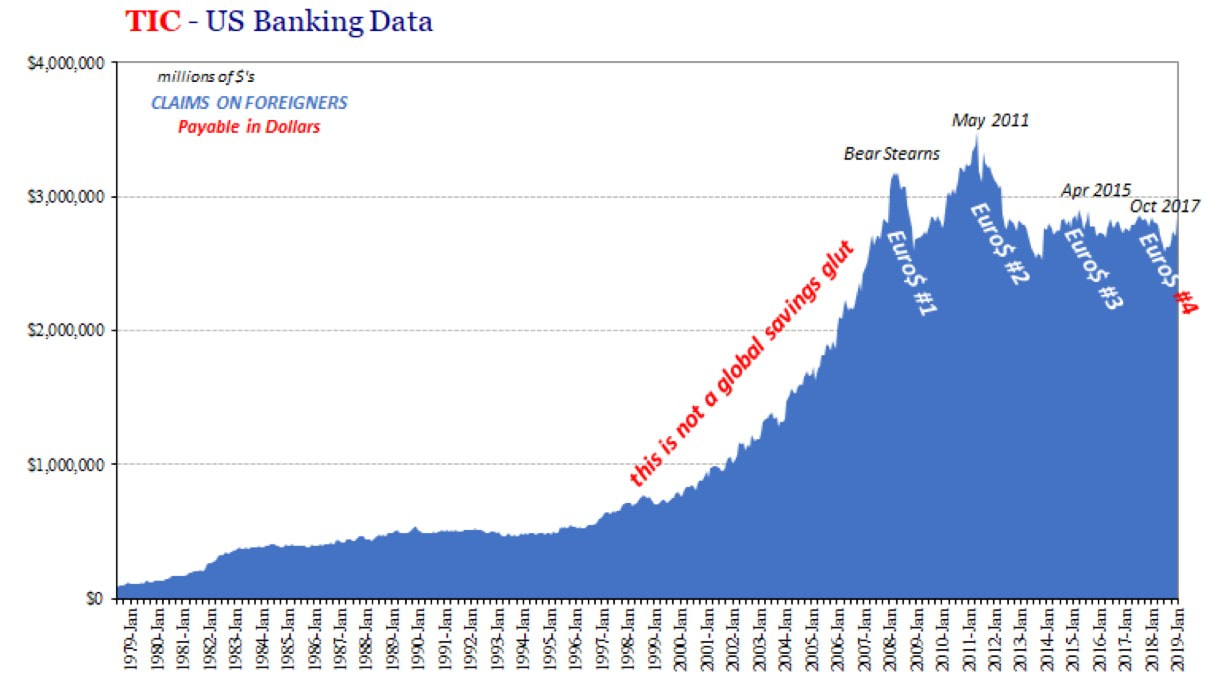

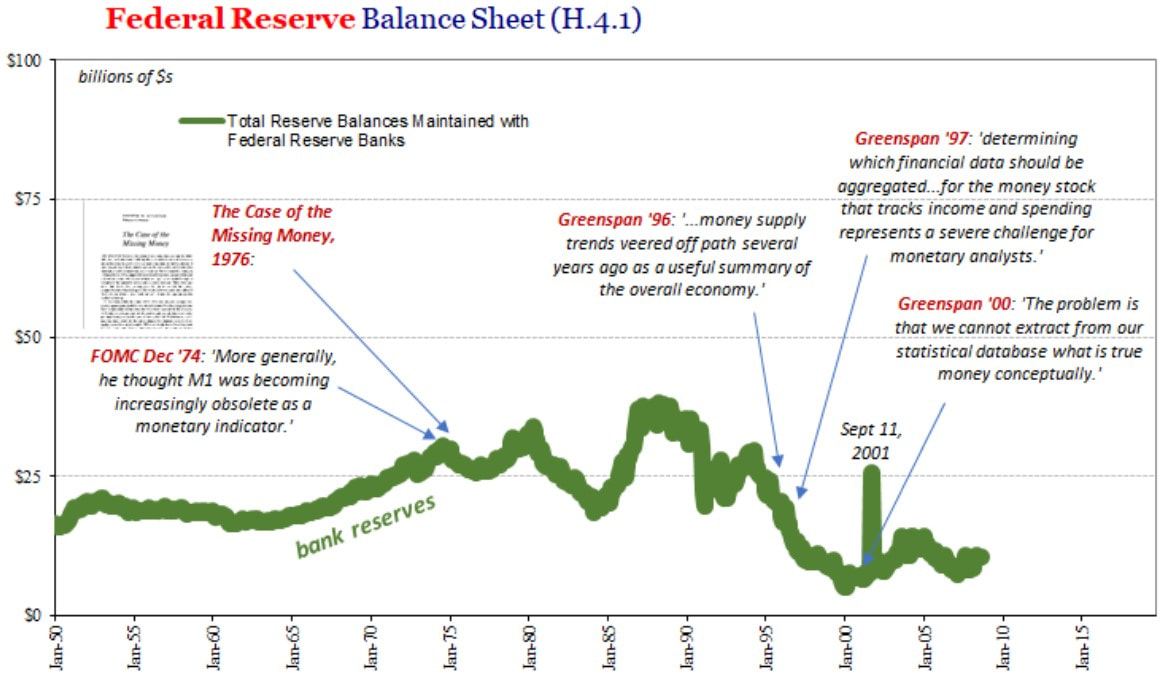

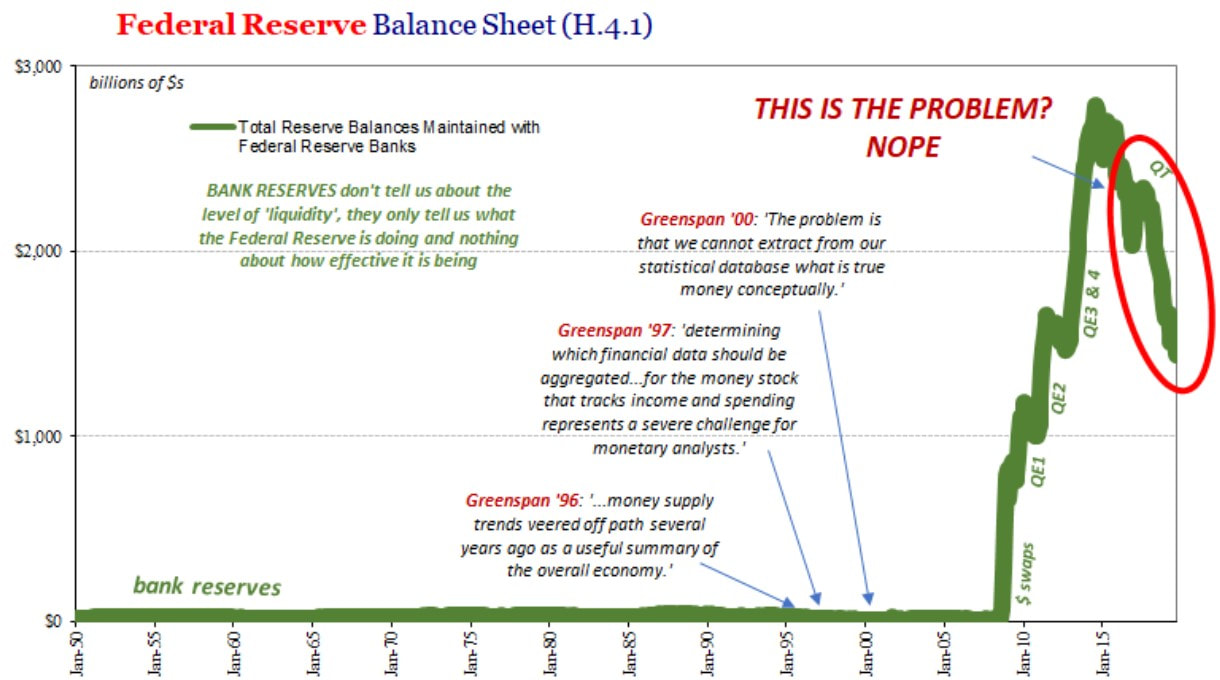

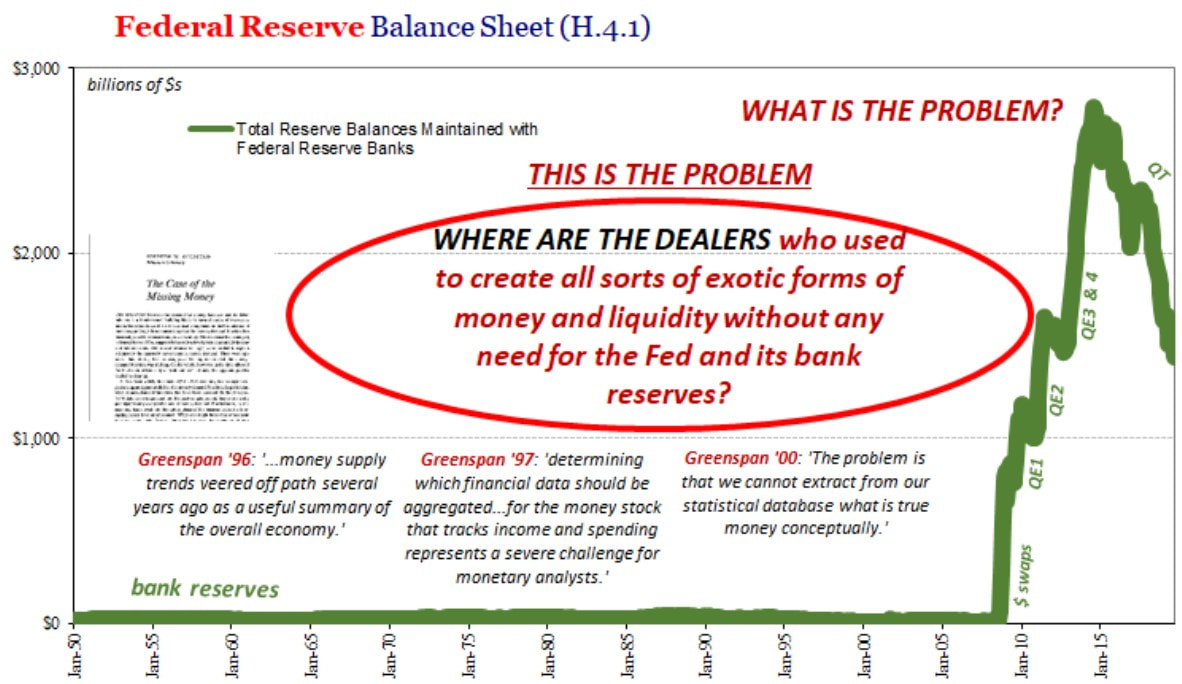

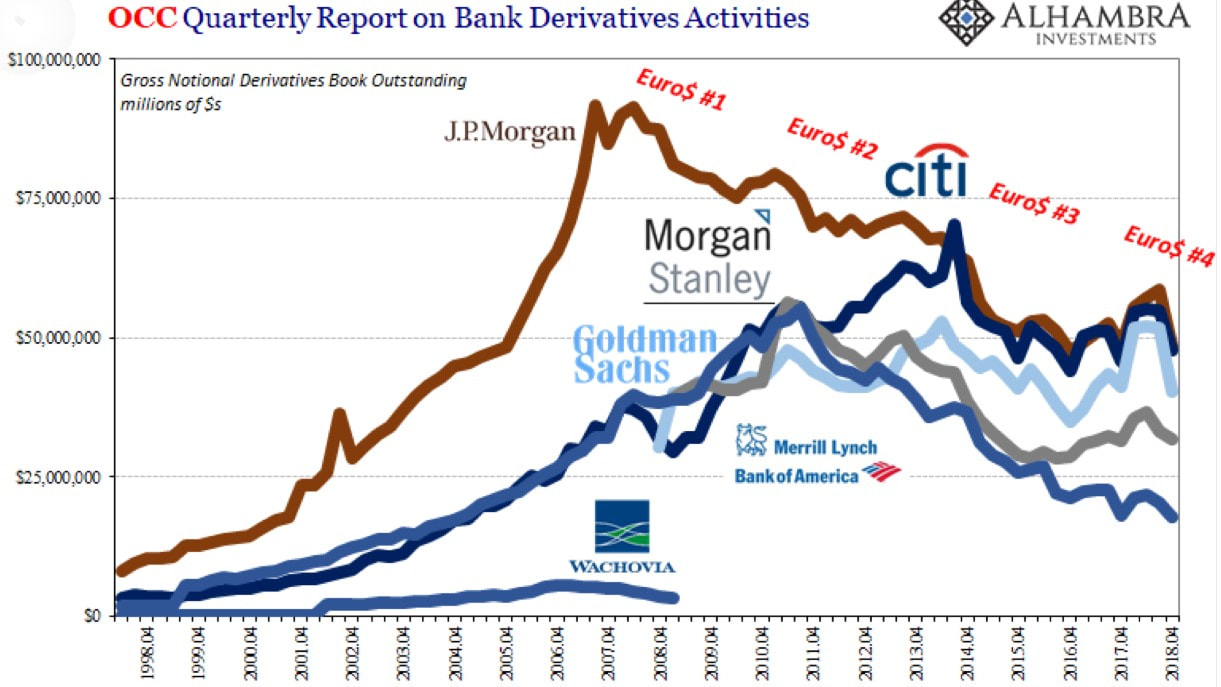

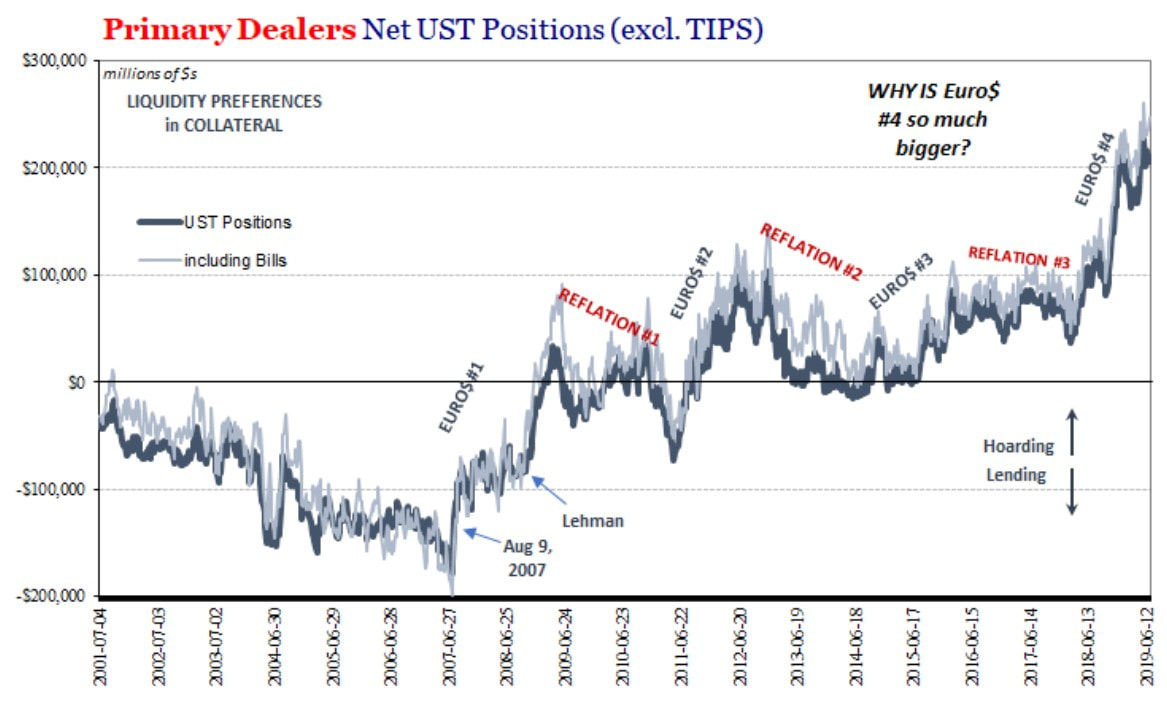

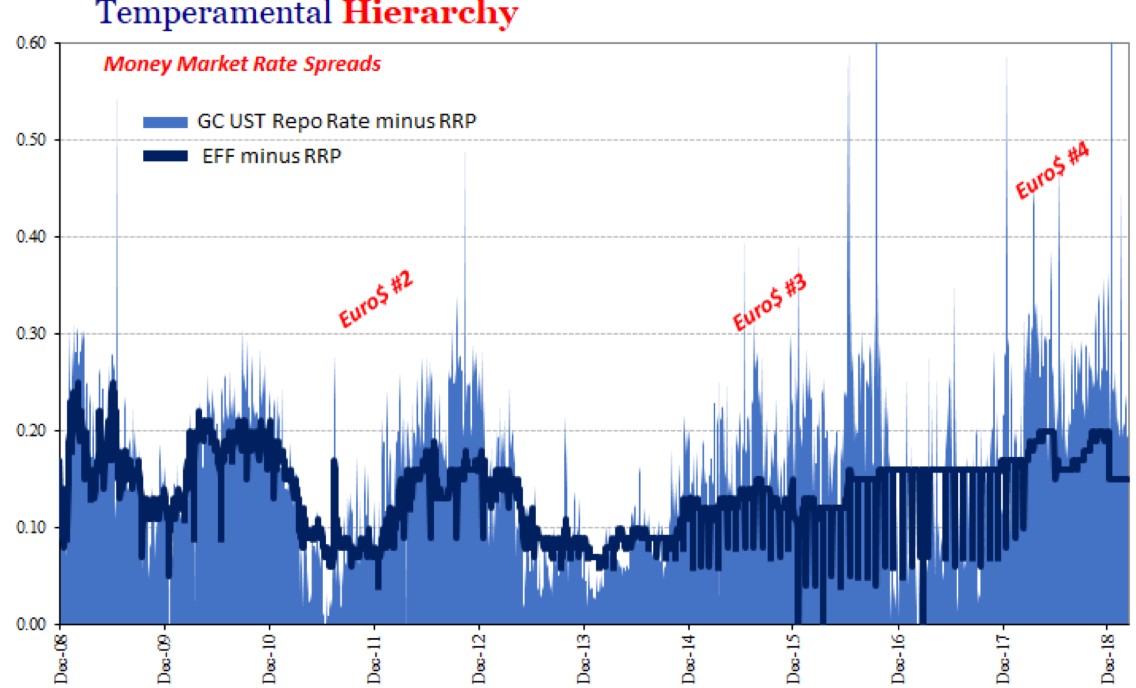

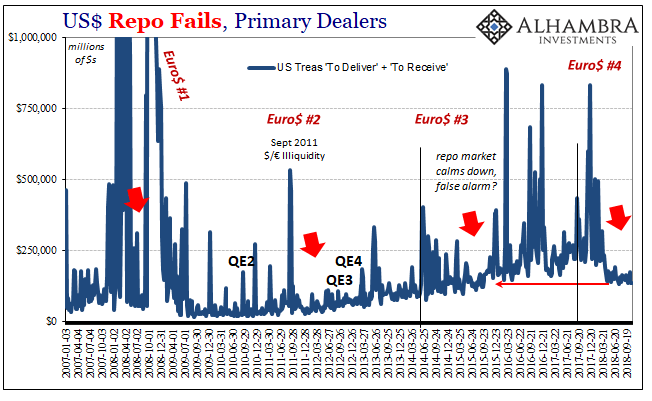

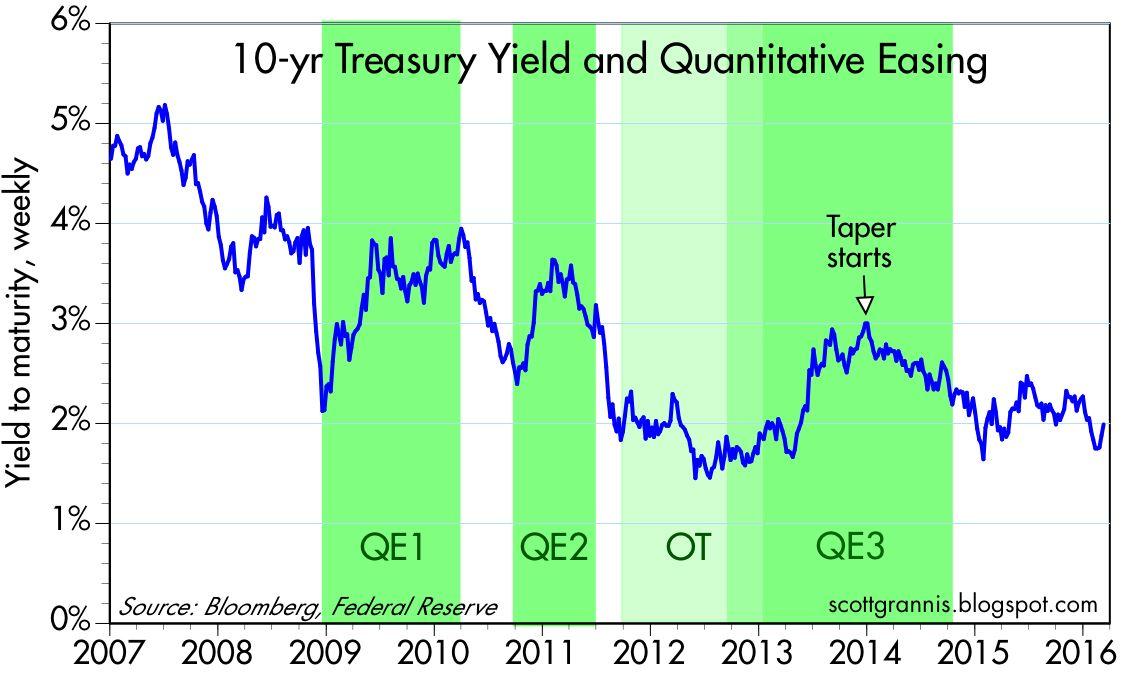

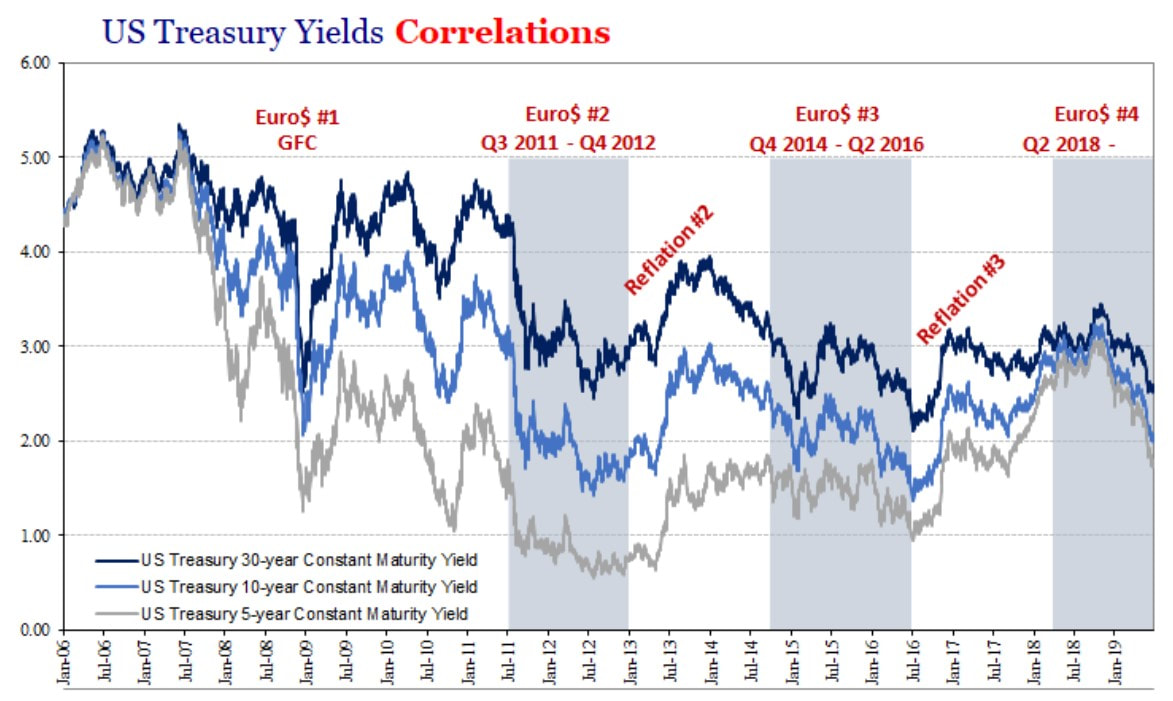

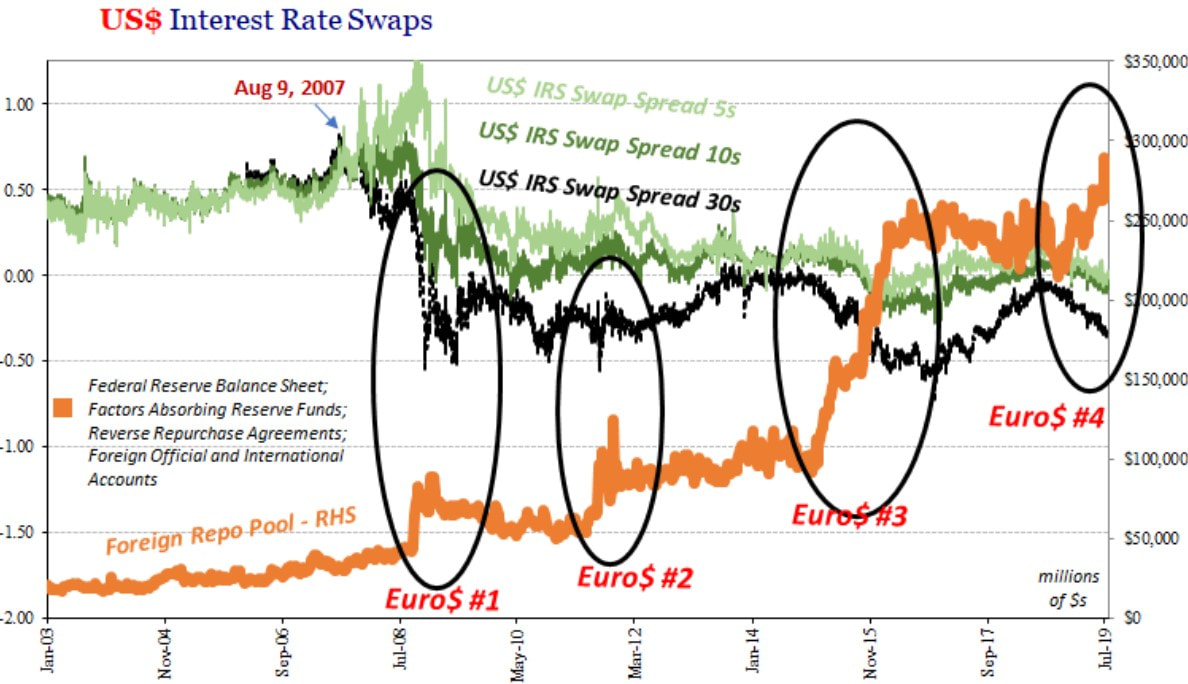

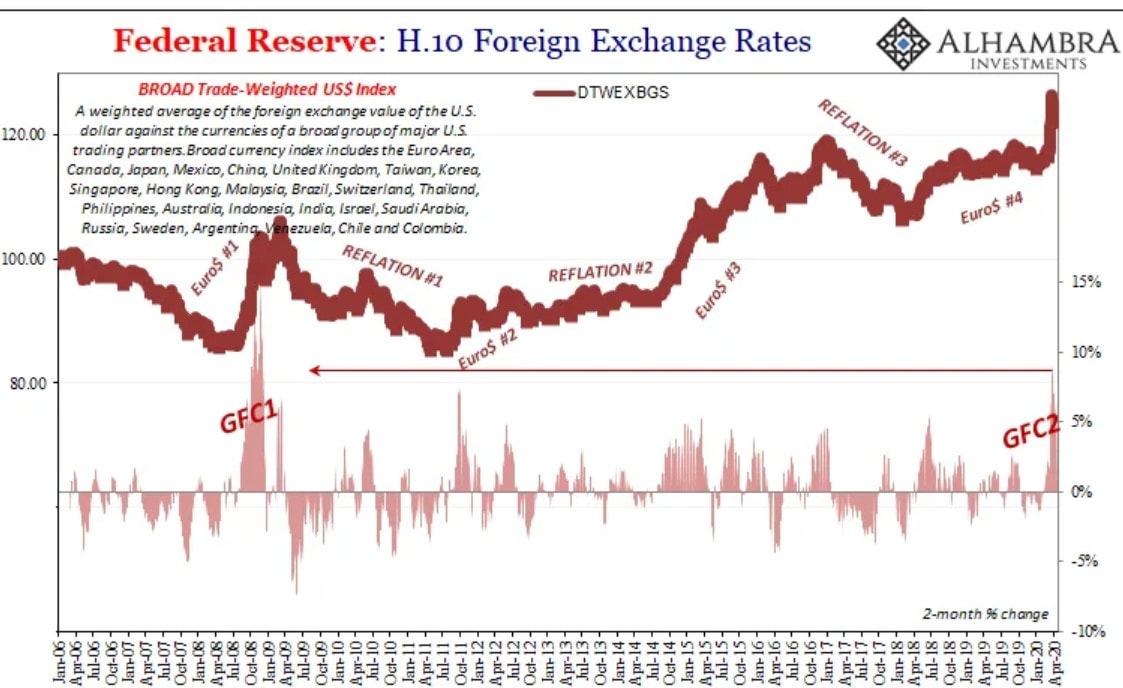

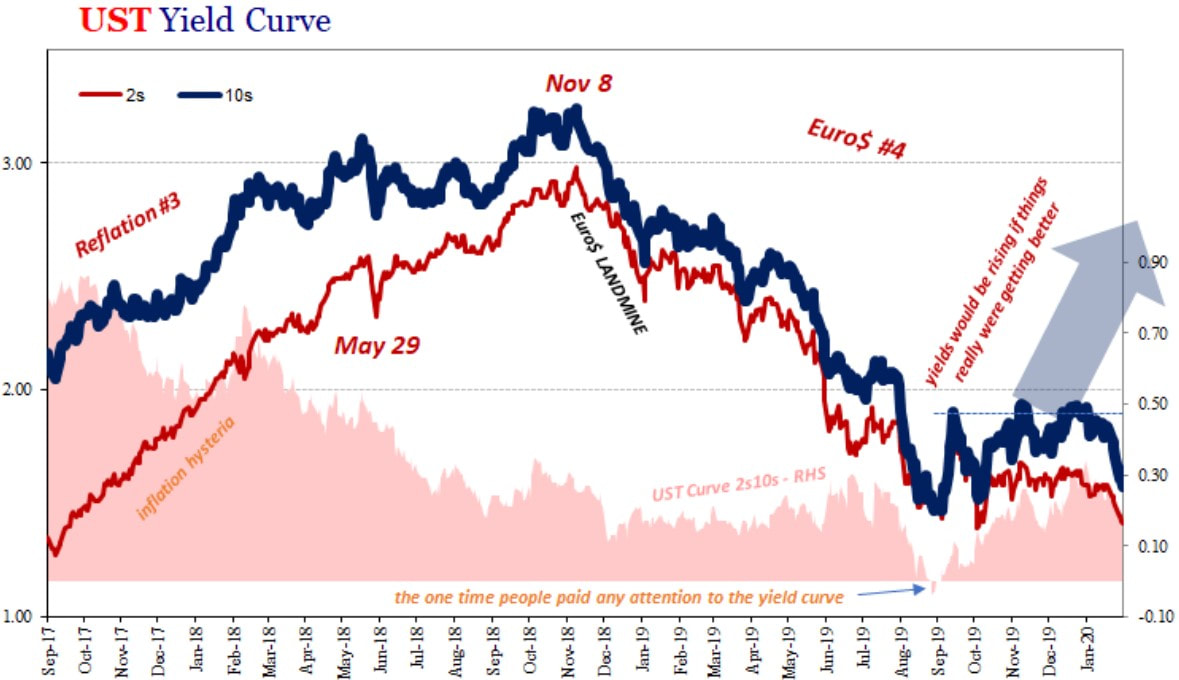

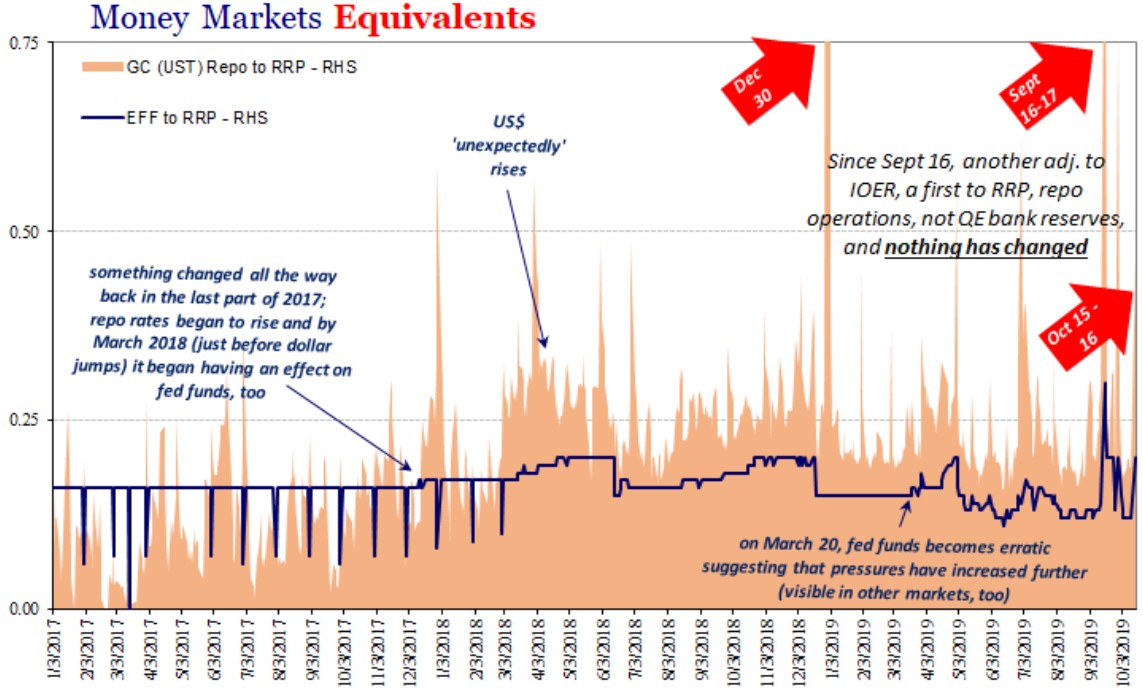

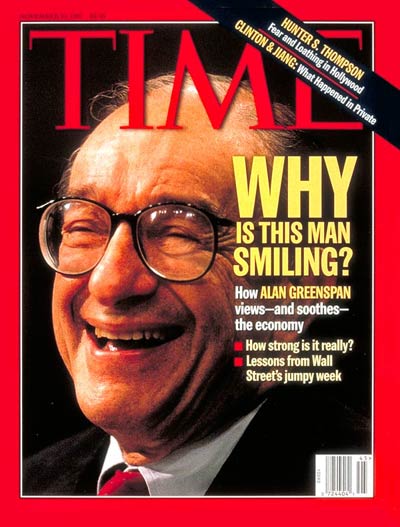

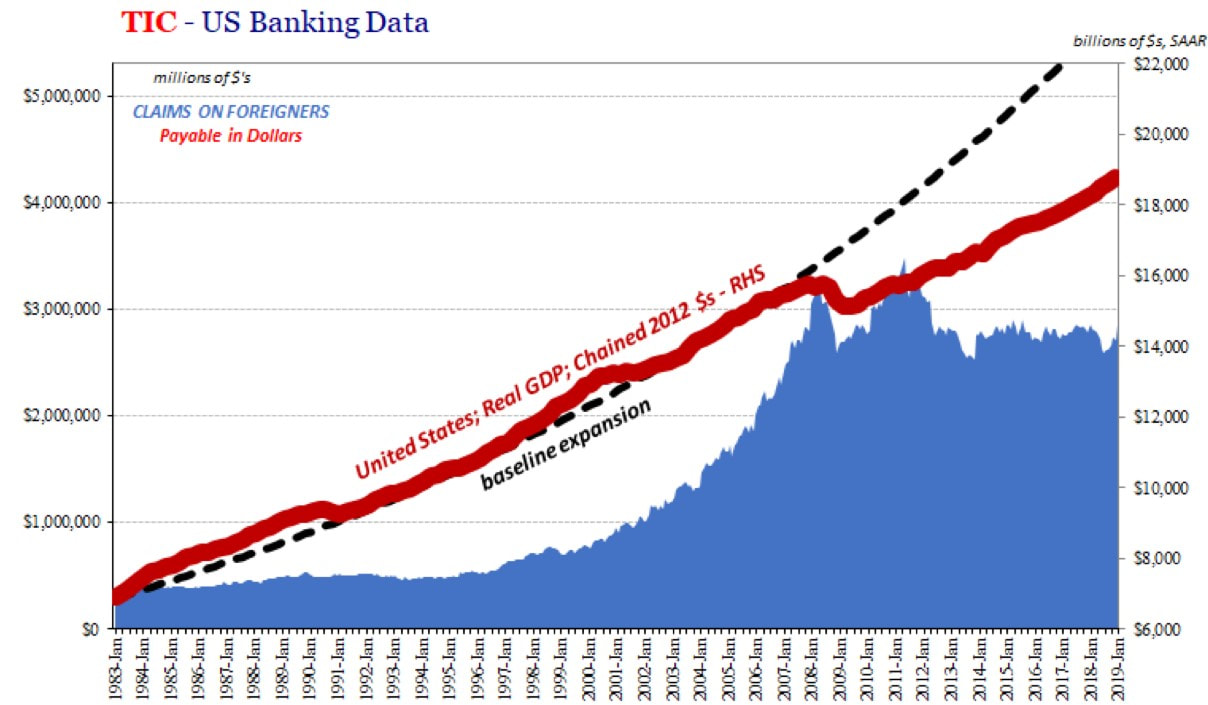

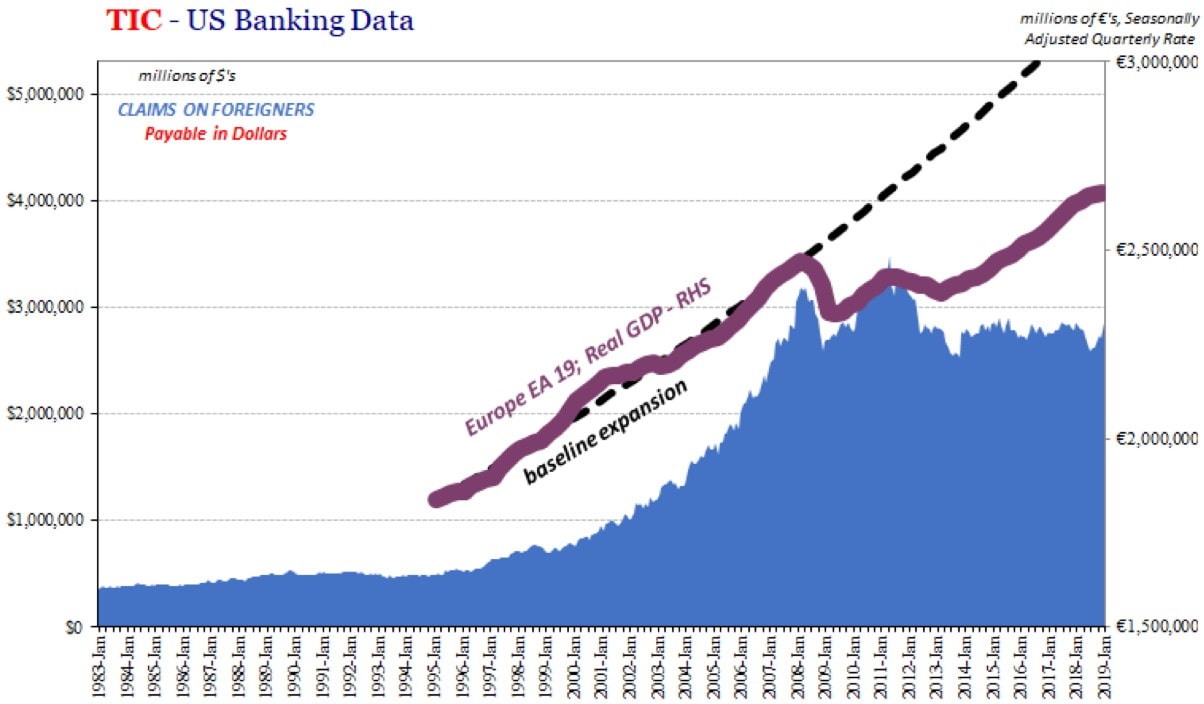

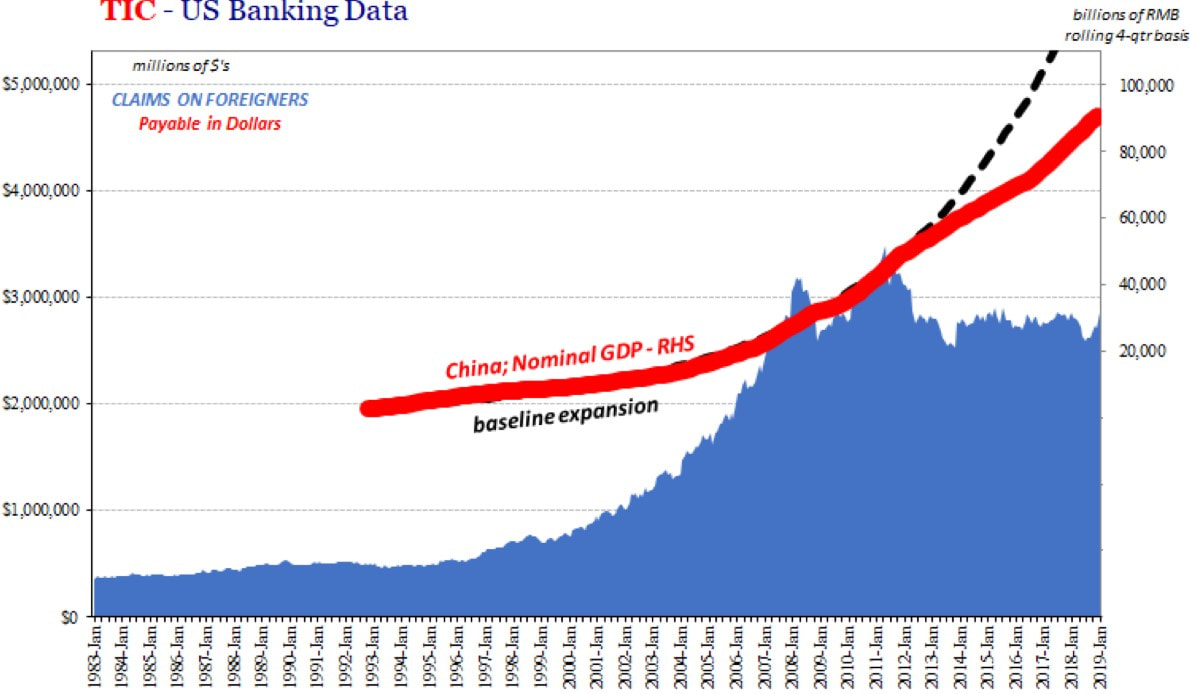

On July 18, 2008, George W. Bush commented at a private political fundraiser in Houston, Texas that "Wall Street got drunk" and that "now it's got a hangover". Although that may had been the case, it seems the financial markets, to this day, have not been able to bounce back. Apparently, the binge drinking practiced mainly since the 1990's made some irreparable damage to the financial system's liver. Despite the central bankers all throughout the world proclaiming to have the cure, the fact is that the hair of the dog provided by their "accommodative" monetary policies has done nothing to put the system back on the growing track. In all seriousness, for some reason the Eurodollar system broke on August 9, 2007 and none of the tools in the central banks' shed managed to fix it. To make matters worse, there are bases to believe the Fed and others are utterly powerless to handle the halt in offshore activity, with their stimulus programmes jacking up nothing more than expectations. On this part 2 of this three-part series, I am going to give explanations for the development of the Eurodollar system being stalled, in addition to its implications on the real economy. Below, the graph presents statistics about US banks and their various cross-border dollar operations. Therefore, that is a proxy for what they might be doing in concert with the unseen foreign counterparties related to this Eurodollar shadow backing activity. As the chart shows, after the GFC, further episodes pertaining to the dollar shortages or funding gap have taken place periodically, apparently every two years or so. Using the designations of Jeff Snider from Alhambra Investment Partners, there have been four Eurodollar events of turmoil. The first one was the Global Financial Crisis, which was also the greatest one (so far). A couple years later, in 2011, another one emerged, resulting in the European sovereign debt crisis, having waned by the end of 2012. Then, in late 2014, the third event ensued, hitting the Emerging markets specially hard, with China in particular slowing down, leading to speculations that it would take a "hard landing", which, were it to occur, it would send massive shock waves through the rest of the world. After this one terminating in the middle of 2016, in the second quarter of 2018, the fourth and most recent episode of Eurodollar woe kicked off. As you will see later on, this last one never faded, meaning that we are still trying to shrug it off. Following part one's discussion, because of the evolution of the Eurodollar system, the complexity of overall financing started growing and defining what money was became an increasingly dubious task. In the early 70's, economists began noticing that, even though transactions denominated in US dollars, in both the financial and the real economy, were rising, the quantity of money was not changing accordingly. In fact, as the next graph depicts, traditional forms of money were becoming obsolete, with bank reserves actually contracting. until 2008. During the 90's, Alan Greenspan often complained that the Fed's aggregates for money supply were getting ever more useless to conduct monetary policy. In his famous December 1996 lecture, known for the "irrational exuberance" remarks, he was not denouncing the soaring stock market, which became the dot-com bubble. He was unburdening about his incapability to understand the trends in the financial markets, since his orthodox convictions on the definition of money made him and his fellow colleagues unable to assess whether their policies were supporting sustainable growth or stock and credit bubbles. During the GFC, even with the innovative policies undertaken by the Fed, such as TALF, dollar swaps with other central banks and the mix of facilities (like it is being implemented today) to support the markets, and the rising uncertainty, the reserves on banks remained constant. Only when Lehman Brothers filled for bankruptcy, in September 15 of 2008, did the banks begin to accumulate reserves. Noticing the banks were hoarding cash in their balance sheets instead of loaning it out or conveying it to the economy via some other means, Ben Bernanke and his posse interpreted this as there was not enough supply of money to meet the demand. For central bankers and keynesians in general, the Fed has the power to steer the markets to where it wants to go. By expanding the monetary base, through open market operations, the banks, a.k.a. primary dealers, have more funding capability and, thus, they can provide loans for investment and consumption, stimulating economic growth. Undoubtedly, decreasing the monetary base has the contrary effect on growth. This is what ought to happen in theory. However, in reality this does not transpires, at least not since the Eurodollar inception. The rationale behind quantitative easing was to be a temporary fix for a temporary trouble. The Fed would stand in until the financial system got back on its feet. To the technocrats surprise, the system never managed to go back to its pre-GFC glory days, no matter how many liquidity injections the banks would take. Likewise, removing liquidity through quantitative tightening (QT) is absolutely benign for the financial system in practical terms, though it is a different conversation for expectations and sentiment. Then, why did it not work? The banks and the other banking institutions that participate in this sketchy Eurodollar system lost their confidence in the system. Prior to the GFC, everybody thought there were no risks attached to their activities. After all, due to ingenious derivative products brought by the marvel of financial engineering, everyone was hedged against all kinds of risk. Adding some baseless faith in central banks to the mix, we ended up with markets where participants were fully convinced the system could grow incessantly. Accordingly, in 2008, reality set in and everybody learned that their convictions in this system were absurd. Unfortunately, most of them still believe the Fed and the other central banks have the faculty to get the financial markets and the real economy booming once again. Nevertheless, the system has not recovered on account of the halt or even decline in the "shadow money". Seeing that shadow bankers no longer trust each other, once they realised the system was brimming with risks, their activities became relatively more modest and aware of the dangers. As a result, in each episode of financial distress, the banks grew more wary of the risks in the system. In spite of their derivative holdings being reduced after each event, by and large, the banks would eventually return expanding their derivative activities, indicating the shadow banking system was becoming more vivacious. However, this would only last for awhile. Like the graph below exposes, each peak in activity would be lower than the previous one, as well as each trough getting lower each time. With the growing awareness of the perceived risk in the system, banks started positioning in an ever safer stance. When the GFC kicked off, the primary dealers reversed course and began accumulating US Treasury securities, especially after the Lehman insolvency. The short-term Treasuries, the T-bills, were particularly preferred for collateral purposes. As I explained in part one, the T-bills are the most pristine collateral. Because structured products that are used as collateral, like MBS, CLO and other ABS, are deemed riskier during periods of financial distress, banking institutions stop accepting them as collateral in the repo operations. This means that when times are bad, inasmuch as market participants have a fair amount of T-bills in their possession, they can use them to get liquidity without any difficulty. Additionally, amidst these episodes, the EFF rate - which is the unsecured, weighted-average rate for all of the transactions of reserves among depository institutions at the Fed -, along with the rates on overnight repo transactions secured by Treasury securities, which the most used one is the General Collateral UST rate, climb up and in times of relative lull they go wane down. However, the typical hierarchy inverts in these periods. Despite the repos being a safer means to get funding, implying a lower rate than the EFF one, which is what happens in normal times, throughout the episodes of financial trouble, the repo rate jumps much higher, surpassing the the EFF rate. This occurs for interest rate are prices and, consequently, behave like such. The EFF rate cranks up due to increasing distrust in the system and higher counterparty risk, leading banks to be less willing to "supply" their funds, implying a greater price to get the funding. Similarly, the rush to ensure financial institutions are able to get financing makes the demand for the best quality collateral to balloon, spiking the repo rate. Since the repo rate shoots up more intensely than the EFF rate, this signifies the problem of the Eurodollar system lies in the collateral. Accordingly, the repurchase agreements that do not materialise, which are known as repo fails, proliferates in these events, because the funds providers cease to accept the low quality collateral. Moreover, another indicator the system never recovered and the Fed's efforts fell short of expectations is the performance of the long-term Treasuries. Looking at the chart on the right, one can see that during the events of distress, the demand for Treasuries strengthens, forcing yields to plunge. The reason is that market participants start speculating the financial conditions are, or close to, deteriorating and, as a result, they would begin switching to safe-haven positions. Considering the graph on the left, quantitative easing did in fact managed to ease the financial conditions. Yet, every time the Fed halted this asset purchase programme, the benchmark 10-year Treasury would reverse course and commence its decline, as well as another Eurodollar event would arise. Seeing that the financial activity would only reflate with the interventions from the Fed, this signals that the shadow banking could no longer return to its heyday on its own. Hence, the financial system became addicted to the Fed's easy money. Moving on to interest rate swaps, these in tandem with the Treasuries yields make up another measure of the banks' balance sheet capacity: interest rate swap spread. Swap spreads are essentially an indicator of the desire to hedge risk, the cost of that hedge, and the overall liquidity of the market. The more people who want to swap out of their risk exposures, the more they must be willing to pay to induce others to accept that risk. Therefore, larger swap spreads means there is a higher general level of risk aversion in the marketplace. It is also a gauge of systemic risk. When there is a swell of desire to reduce risk, spreads widen tremendously. It is also a sign that liquidity is greatly reduced, as was the case during the financial crisis of 2008. Even tough this was the case up to the GFC, the interest rate swap spreads have since then behaved in a different fashion. After the GFC, these spreads have tighten gradually, even entering negative territory. On account of the loss of confidence in the system and the sudden realisation that the financial system actually carried risk, regardless of the breakthroughs in financial products, market participants stopped viewing these kind of instruments as incapable of hedging risks. Consequently, the players in the Eurodollar system had to find another source of liquidity to get the dollars to satisfy their US dollar-denominated liabilities, whenever the financial constraints cropped up. So, the financial institutions in this offshore dollar system turned to the central banks in their jurisdictions in order to get the funding needed. Inasmuch as the Federal Reserve is the only one capable of creating the greenback, the foreign central banks and other monetary authorities have to go to the Fed to get those dollars. One of the ways they can get the dollars, which is also the most used one, is through repurchase agreements. These foreign institutions temporarily sell some of their holdings in US Treasuries so as to get the dollars, which they then give to their financial institutions. In addition, as the next chart demonstrates, during the Eurodollar episodes, these foreign entities are extremely active in these repo operations with the Fed, in order to quench the offshore participants' thirst for dollars. In these periods of financial stress, the Eurodollar players, in their quest to come up with dollars to meet their obligations, end up pushing the dollar higher. There is a common misconception that the strong dollar causes financial turmoil all around the globe, bringing about less economic growth for the world as a whole. Au contraire, the rising dollar is not the cause but the effect. For whatever reason - each episode has its own particularities -, the Eurodollar system periodically goes through woes, which, as I described, drives the dollar to greater magnitudes. Evidently, this appreciation of the greenback reinforces the financial distresses, impairing the real global economy even more. Therefore, whenever the USD is surging, it is a sign troubles in the financial system are emerging and will soon become apparent. In this day and age, the soaring dollar accompanied three episodes of affliction when the Eurodollar system ventured on the brink of collapse. The fourth one commenced on the early part of 2018. The graph on the right portrays the onset of this last event, when the repo rate swelled and consistently stayed above the EFF rate, which in turn became more erratic. As a result, the dollar mounted up. Moving on to the graph on the left, the Treasuries yields began, on November 8, transmitting the message that troubles in the financial system were brewing. Then, on August 27 of last year, one of the most daunting indicators for market participants sprang up. The yields of the 2 and 10-year Treasuries inverted. Historically, this yield inversion has preceded every recession since the late 1970's. Once this occurs, it is almost certain an economic contraction is on the cards. Hence, the primary dealers and other depository institutions, interpreting the inversion as impending troubles, turned more reluctant to provide funds among each other. Furthermore, the search for liquidity became more difficult, which meant the repo rate surged due to increased demand for these operations. On part 3 of this series, I am going to expand more on the present Eurodollar event. Moreover, you may have figured out by now that the Fed, despite its claim that it "provides the nation with a safe, flexible and stable monetary and financial system", the truth is that they are far from achieving that claim, because they do not know how to do it and, to add insult to injury, even if they did, they are powerless in their efforts to curb the Eurodollar caprices. The Fed's policies, as well as the myriad of facilities implemented in the midst of the GFC, do virtually nothing to solve the distresses of dollar shortages during financial panics. The only thing the Fed can do, with the help of the financial media and the keynesian technocrats spread worldwide, is try to persuade market participants that it is ubiquitous and able to support or rescue the financial system no matter what. The truth is that they can only follow the signals given by the markets and respond to them - rather late I should add - so as to create the illusion of backstopping the markets' woes and, thus, maintain the system afloat. In all fairness, the central bankers and the media have been successful in duping everybody that they do in fact have the control of the system's helm. Fortunately, the sham will be exposed very soon. Finally, the system broke down in the summer of 2007 simply because there was, and still is, too much debt. As I have been discussing since part one, on account of diminishing good collateral and greater counterparty risk, the financialisation process of the global economy came out of the GFC severily hindered. Owing to the fact we live in a world where the tail wags the dog, meaning that the health of the financial system regulates the performance of the real economy, the near stall of the financialisation phenomenon prompted the economic development in taking its toll, especially in the developed economies, as the following graphs show. In a nutshell, the Eurodollar has been running on fumes. To conclude, before the 2008 crisis, the shadow Eurodollar system grew exponentially, due to the ludicrous idea that financial engineering had managed to curb the risks taken by the market participants. After the GFC, that belief went out the window, turning everybody more cautious.

In spite of all the efforts made by the central bankers, the system never recouped its pre-GFC effervescent trajectory. However, the media has at least made everyone believe the Fed saved the financial system and the economy, even though everything points that conditions have actually got worse. On the last part of this three-part series, I am going to expound on the current financial panic. Specifically, on whether the crisis is close to its culmination or it is only beginning, and I am going to weigh in on the ability this system and the central bankers have to endure this blow.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDaniel Gomes Luís Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed